Editor’s Note: WOHM would like to introduce freelance writer Saidah Ali Wilson, who succinctly chronicled her experience at Northwest Hip-Hop Fest while exploring a phenomenon detrimental to the Portland Hip-Hop scene and coining the phrase “BYOF”. Enjoy!

~Mac Smiff, Editor-in-Chief

8:45PM

Big Mo – I haven’t been to a lot of hip-hop festivals, but if this is how they all start, I’m hooked. Where has this guy been all my life? Self-deprecating, sarcastic, and totally comfortable in his own skin, Mohammed Alkhadher owned the stage, owned the mic and owned the crowd. All twenty-five of us. Which brings up a Big Question: where the hell was everyone? I mean, a music festival isn’t a party; you don’t show up fashionably late. You get there, on time, to see every act, hear every track and meet every artist. You never know who/what you’ll find at a music festival, even at 8:45. Big Mo definitely deserved a better time slot, but then again, all the self-proclaimed hip-hop heads out there should have just shown up.

9:00PM

Portland definitely went on to stay weird. Which is not to say that the artists that followed Big Mo weren’t talented; they were. DJ Sneakers, Commenter-E, Risky Star, DJ Fatboy, and Easy McCoy kept good music coming. But where was everyone? The tickets were cheap, the venue was convenient, and artists were good. But the space was dead. The few that were there seemed totally disconnected: Big Mo tried to jokingly single out stoic table dwellers and DJ Klyph tried to lead by example, but to no avail.

Oh, and by the way, the audience at Kelly’s was impressively White (I’m not sure if there were more than fifteen or twenty people of color in the room at any point Thursday night). I realize that this is pretty much the palest metro in America, but still; I’ve seen Black and brown fans come out for the Lifesavas and Speaker Minds.

It’s 10PM on a Thursday night; do you know where your local emcee is performing? Apparently not.

11:00PM

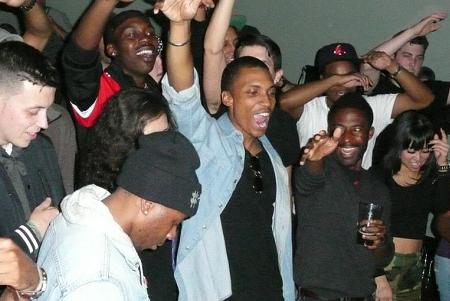

Where the hell did all these people come from? In about fifteen minutes, the room went from nearly-empty to standing-room-only. Seriously. Although, oddly, I was seeing a LOT of (White) hipsters.

Turns out, the funk/soul/groove band Dirty Revival (and a hundred or so of their closest friends) had taken over. Interestingly enough, although I definitely loved their show, and I definitely appreciated that they and their fans didn’t just take off after their set, this was definitely not what we usually consider hip-hop. Yeah, they had an emcee. But even they informed the crowd that they were there to supply the “& Funk” that’s technically supposed to be attached to the “NW Hip-Hop Festival” billing. And funky they were. But they were also an entirely different type of act and they definitely brought an entirely different crowd with them.

Disappointingly, even Cool Nutz, the “mayor of Portland hip-hop,” didn’t draw a crowd. Dirty Revival performers stayed for his set, and so did a large portion of their fan base, which filled out the room. But it was pretty obvious that engaged and energetic as they were, they weren’t incredibly familiar with him as an artist. There were a handful of obvious Cool Nutz fans, but most of the crowd that stuck around for the rest of the night was pretty clearly there because Dirty Revival stayed for the rest of the acts.

Fast forward to Friday night.

9:00PM

A few more faces. A lot more color. Great music.

Dead. As. Hell.

I was just about to go drown my disappointment in vodka when, wonder of wonders, people started showing up. Load B fans, Zoo fans, Stewart Villain fans, Cassow fans. The big names brought big crowds with them, and their big crowds brought big energy. By 9:45, the energy, the headcount, the volume, everything, was up. It was still weird, somehow, but less weird.

10PM

As Kelly’s started to really pack out and the crowd got really crazy, I had a chance to chat with one of the biggest NWHHF promoters, KZME’s DJ Klyph. We started out with the most obvious subject; what the hell happened last night?

His answer?

He shook his head and said, simply, “This is Portland.”

“Portland is different,” he tells me. “It’s like, a lot of people here don’t know how this works.”

Basically, he explained, Portland is a pretty transitional city. Young, trendy, and increasingly non-native Portlanders tend to lack a lot of the foundational concepts and relational roots that cultural development, specifically, hip-hop cultural development, requires. Fans don’t know how to be fans, and artists don’t know how to be artists. There is no community, no engagement. Artists like Stewart Villain and Blazé have described the problem as a result of jealousy. DJ Klyph says he’s heard that before, but he disagrees.

“Hip-hop just doesn’t have the support here. The artists don’t support other artists…. Everyone just wants to be the star… and they’re surrounded by their friends who tell them, ‘you’re so great!’ and so they never develop the skills they need to really get themselves out there… And fans, they support their friends and that’s it. They don’t care about anyone else’s work.”

I point out that music, and hip-hop in particular, is very dependent on relationships, on community. That collaboration and cooperation make everyone better. Peeved, I exclaimed, “You can’t make good art in a vacuum!”

“Right.”

When I ask DJ Klyph what he would most like to see in the hip-hop community, and specifically at NWHHF, in the next few years, he doesn’t think twice.

“Education. I would like to see more education.”

Shrugging, he continues, “I’d love to see more young artists learn from the veterans. But right now, a lot of the younger artists are like, “okay, you’re older, you’ve had your time, but now it’s my time. They don’t really want to watch and learn from… how [the previous generation of] artists did it. We live in a time when I can’t tell a young artist, “you’re not a good emcee,” or “you need to do more work,” or “this isn’t your thing.” DJ Klyph continued, “I mean, everyone doesn’t need to be an emcee. Everyone doesn’t need a mic. Everyone doesn’t need to be onstage. But this [NWHHF] could help people find their ‘thing’…“

“Because hip-hop is not just being onstage.”

“Right… Someone’s gotta promote, someone’s gotta make posters, someone’s gotta do sound, somone’s gotta set up, someone’s gotta be on the radio, like me… But people get offended. They’re just like, “you’re a hater.””

I roll my eyes. “I hate that word. “Hater.” It’s such a conversation killer. You can’t have a conversation after someone throws out that word.”

“Right?”

Before we head back into the venue, DJ Klyph tells me, “I’m a fan first. I love hip-hop… I respect it as an art… that’s what I really want from this. I want people to respect the art.”

Friday night at Kelly’s was really good. Like, amazing. And Saturday night, I got to bounce back and forth between Kelly’s and Ash Street, and every single show was good. But here’s the real killer; almost no one came for the festival. Yeah, people came to the festival, but almost everyone was there to support a particular artist, and then, fuck everyone else, they were out. Not everyone, but a lot. Most artists didn’t stick around for other artist’s sets, and most fans were just there to hang out with a particular group that was supporting a particular act. There was very little interaction (much less collaboration) between artists, and the community spirit that I’ve always experienced at music festivals was totally absent.

DJ Klyph pointed out that Portlanders like to complain about the lack of spotlight on local, listen-worthy artists. But, he insists, they don’t get what they need to do to get that spotlight.

“Hip-hop is regional. A region has to support their artists. We have to be like, “We’re going to take this artist and push this artist up…” Because if that artist gets big then there will be more focus on this area, on Portland. Then other people get seen. But people don’t get that here.”